SOLID Design Principles

SOLID is one of the most popular sets of design principles in object-oriented software development. It’s a mnemonic acronym for the following five design principles:

S - Single Responsibility Principle

O - Open-Closed Principle

L - Liskov Substitution Principle

I - Interface Segregation Principle

D - Dependency Inversion

Single Responsibility Principle

A class should have just a single reason to change. A single class should have one primary responsibility instead of taking on a lots and lots of different responsibilities.

For e.g. let make a simple Journal class. This class is going to store our most intimate thoughts. Features of the program should be able to

- Add new entry

- Remove entry

- Save entries to storage system

- Load/fetch entries from storage system

/**

* BAD EXAMPLE

*/

class Journal {

private final List<String> entries = new ArrayList<>();

private static int count = 0;

public void addEntry(String text) {

entries.add("" + (++count) + ": " + text);

}

public void removeEntry(int index) {

entries.remove(index);

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.join(System.lineSeparator(), entries);

}

public void saveToFile(String text, String filename, boolean overwrite) throws FileNotFoundException {

// Omitted

}

public void loadFromFile(String filename) {

// Omitted

}

}Essentially, the example above is a violation of the Single Responsibility Principle (SRP) because the Journal class has taken on addition concerns. We're not only adding and removing the entries from the Journal but also handling the persistence (saving and loading the file from storage system). Persistence here, is a separate concern. Now what we can do is move the persistence concern to a whole new class in order to adhere to the SRP.

/**

* GOOD EXAMPLE

*/

class Journal {

private final List<String> entries = new ArrayList<>();

// Total number of entries across however many journals we make

private static int count = 0;

public void addEntry(String text) {

entries.add("" + (++count) + ": " + text);

}

public void removeEntry(int index) {

entries.remove(index);

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return String.join(System.lineSeparator(), entries);

}

}

class Persistence {

public void saveToFile(String text, String filename, boolean overwrite) throws FileNotFoundException {

if (overwrite || new File(filename).exists()) {

try (PrintStream out = new PrintStream(filename)) {

out.println(text);

}

}

}

// Omitted

public void loadFromFile(String filename) {

}

}

class App {

public static void main(String[] args) throws Exception {

Journal j = new Journal();

j.addEntry("I cooked today");

j.addEntry("I ran 4km");

Persistence p = new Persistence();

String filename = "journal.txt";

p.saveToFile(j.toString(), filename, true);

}

}So the take away is that the SRP basically tries to force you to put just one responsibility into any single class. If you add more responsibilities you'll end up with god object which can be very unmanageable and very difficult to work and refactor later on.

Open-Closed Principle

It's now time for the O in SOLID, known as the open-closed principle (OCP). Simply put, classes should be open for extension but closed for modification. In doing so, we stop ourselves from modifying existing code and causing potential new bugs in an otherwise happy application.

Of course, the one exception to the rule is when fixing bugs in existing code.

Let's suppose you're building a program that will allow users to filter the products by a specific criteria i.e. color, size.

/**

* BAD EXAMPLE

*/

enum Color {

RED, GREEN, BLUE

}

enum Size {

SMALL, MEDIUM, LARGE

}

class Product {

public String name;

public Color color;

public Size size;

public Product(String name, Color color, Size size) {

this.name = name;

this.color = color;

this.size = size;

}

}

class ProductFilter {

public Stream<Product> filterByColor(List<Product> products, Color color) {

return products.stream().filter(p -> p.color == color);

}

public Stream<Product> filterBySize(List<Product> products, Size size) {

return products.stream().filter(p -> p.size == size);

}

public Stream<Product> filterBySizeAndColor(List<Product> products, Size size, Color color) {

return products.stream().filter(p -> p.size == size && p.color == color);

}

// state space explosion

// 3 criteria = 7 methods

}

class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Product apple = new Product("Apple", Color.GREEN, Size.SMALL);

Product tree = new Product("Tree", Color.GREEN, Size.LARGE);

Product house = new Product("house", Color.BLUE, Size.LARGE);

List<Product> products = List.of(apple, tree, house);

ProductFilter pf = new ProductFilter();

System.out.println("Green products");

pf.filterByColor(products, Color.GREEN).forEach(p -> System.out.println(" - " + p.name + " is green"));

}

}Here, we're creating a three different methods each to filter using the different product criteria. The problem here is that this code is okay for two criteria but if we were to add single new criteria for e.g. price, we'll end up with 7 methods to cover every intersection which can be very problematic. This, would be a violation of OCP since the whole point of the OCP is to be open for extension but closed for modification.

/**

* GOOD EXAMPLE

*/

enum Color {

RED, GREEN, BLUE

}

enum Size {

SMALL, MEDIUM, LARGE

}

class Product {

public String name;

public Color color;

public Size size;

public Product(String name, Color color, Size size) {

this.name = name;

this.color = color;

this.size = size;

}

}

interface Specification<T> {

boolean isSatisfied(T item);

}

interface Filter<T> {

Stream<T> filter(List<T> items, Specification<T> spec);

}

class ColorSpecification implements Specification<Product> {

private Color color;

public ColorSpecification(Color color) {

this.color = color;

}

@Override

public boolean isSatisfied(Product p) {

return p.color == color;

}

}

class SizeSpecification implements Specification<Product> {

private Size size;

public SizeSpecification(Size size) {

this.size = size;

}

@Override

public boolean isSatisfied(Product p) {

return p.size == size;

}

}

/**

* Combinator - combines two filters together

*/

class AndSpecification<T> implements Specification<T> {

private Specification<T> first, second;

public AndSpecification(Specification<T> first, Specification<T> second) {

this.first = first;

this.second = second;

}

@Override

public boolean isSatisfied(T item) {

return first.isSatisfied(item) && second.isSatisfied(item);

}

}

class BetterFilter implements Filter<Product> {

@Override

public Stream<Product> filter(List<Product> items, Specification<Product> spec) {

return items.stream().filter(p -> spec.isSatisfied(p));

}

}

class App {

public static void main(String[] args) {

Product apple = new Product("Apple", Color.GREEN, Size.SMALL);

Product tree = new Product("Tree", Color.GREEN, Size.LARGE);

Product house = new Product("house", Color.BLUE, Size.LARGE);

List<Product> products = List.of(apple, tree, house);

BetterFilter bf = new BetterFilter();

System.out.println("Green products:");

bf.filter(products, new ColorSpecification(Color.GREEN))

.forEach(p -> System.out.println(" - " + p.name + " is green"));

System.out.println("Large blue items:");

bf.filter(products, new AndSpecification<>(new ColorSpecification(Color.BLUE), new SizeSpecification(Size.LARGE)))

.forEach(p -> System.out.println(" - " + p.name + " is large and blue"));

}

}Above code will yield the same output but the now upside is that if we want an additional specification, we don't need to jump into existing classes and modify them. Hence the take away is that we only have to use the inheritance and implementations of interfaces and at no point in time would we want to actually jump back into existing code and modify it to add new additional functionalities.

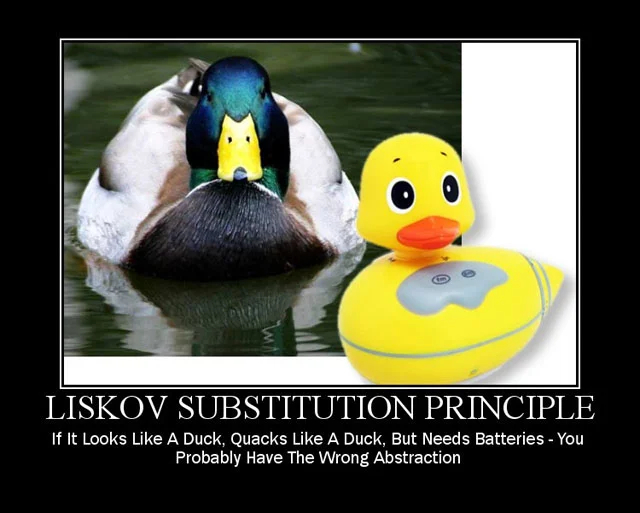

Liskov Substitution Principle

Next on our list is Liskov substitution principle (LSP). The idea of the LSP is you should be able to substitute a subclass for a base class. So if you have some API, which takes a base class, you should be able to stick a subclass in there without the things breaking in any way.

The principle defines that objects of a superclass shall be replaceable with objects of its subclasses without breaking the application. That requires the objects of your subclasses to behave in the same way as the objects of your superclass

Let's jump straight to the code to help us understand this concept:

/**

* BAD EXAMPLE

*/

class Rectangle {

protected int width, height;

public Rectangle() {

}

public Rectangle(int width, int height) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

public int getWidth() {

return width;

}

public void setWidth(int width) {

this.width = width;

}

public int getHeight() {

return height;

}

public void setHeight(int height) {

this.height = height;

}

public int getArea() {

return width * height;

}

@Override

public String toString() {

return "Rectangle{" + "width=" + width + ", height=" + height + '}';

}

}

class Square extends Rectangle {

public Square() {

}

public Square(int size) {

width = height = size;

}

@Override

public void setWidth(int width) {

super.setWidth(width);

super.setHeight(width);

}

@Override

public void setHeight(int height) {

super.setHeight(height);

super.setWidth(height);

}

}

class Demo {

static void useIt(Rectangle r) {

int width = r.getWidth();

r.setHeight(10);

// area = w * 10

System.out.println("Expected area of " + (width * 10) + ", got " + r.getArea());

}

public static void main(String[] args) {

Rectangle rc = new Rectangle(2, 3);

useIt(rc);

// Output: Expected area of 20, got 20

Square sq = new Square();

sq.setWidth(5);

useIt(sq);

// Output: Expected area of 50, got 100

}

}LSP states that you should be able to substitute a derived class for a base class. Here, the useIt() method takes a Rectangle object, so it should be possible for userIt() method to take in a Square instead of a Rectangle. But when we tried to do that, things didn't go as expected.

The reason why this happened is because the setter setHeight() that we're using inside useIt() method is a very non-intuitive setter as it makes sense for a Rectangle but doesn't make sense for a Square because setting one would change the other to match it. In this case Square fails the Liskov Substitution Test with Rectangle and the abstraction of having Square inherit from Rectangle is a bad one.

One possible solution would be to simple have some sort of detection whether a Rectangle is a Square or not. So here, you can create a boolean isSquare() method which checks whether something is a Square or not.

class Rectangle{

protected int width, height;

public Rectangle(int width, int height) {

this.width = width;

this.height = height;

}

/**

* Omitted

*/

public boolean isSquare() {

return width == height;

}

}The illustration here is to show you that if you violate the LSP it will result in incorrect code through inheritance. Which is something you'll need to avoid.

Interface Segregation Principle

The I in SOLID stands for interface segregation principle (ISP), and it simply means that larger interfaces should be split into smaller ones. By doing so, we can ensure that implementing classes only need to be concerned about the methods that are of interest to them.

For this example, we're going to try our hands as zookeepers. And more specifically, we'll be working in the bear enclosure.

Let's start with an interface that outlines our roles as a bear keeper:

/**

* BAD EXAMPLE

*/

public interface BearKeeper {

void washTheBear();

void feedTheBear();

void petTheBear();

}As avid zookeepers, we're more than happy to wash and feed our beloved bears. But we're all too aware of the dangers of petting them. Unfortunately, our interface is rather large, and we have no choice but to implement the code to pet the bear. So this is where we come to the ISP, basically very simple idea that you shouldn't put into your interface more than what the client is expected to implement.

Let's fix this by splitting our large interface into three separate ones:

/**

* GOOD EXAMPLE

*/

public interface BearCleaner {

void washTheBear();

}

public interface BearFeeder {

void feedTheBear();

}

public interface BearPetter {

void petTheBear();

}Now, thanks to interface segregation, we're free to implement only the methods that matter to us:

public class BearCarer implements BearCleaner, BearFeeder {

public void washTheBear() {

//I think we missed a spot...

}

public void feedTheBear() {

//Tuna Tuesdays...

}

}And finally, we can leave the dangerous stuff to the reckless people:

public class CrazyPerson implements BearPetter {

public void petTheBear() {

//Good luck with that!

}

}So the takeaway from ISP is that, instead of sticking everything into a single interface like we did for the BearKeeper interface. What we should do is put the absolute minimum amount of code into an interface so that at no point does a client (a developer) has to implement the interface that has a certain method that they don't need at all.

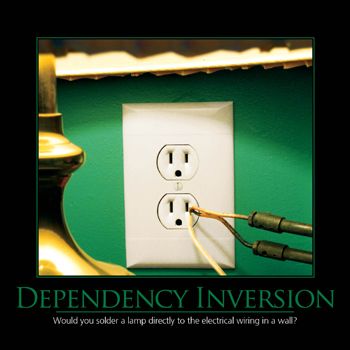

Dependency Inversion Principle

The general idea of this principle is as simple as it is important: High-level modules, which provide complex logic, should be easily reusable and unaffected by changes in low-level modules, which provide utility features. To achieve that, you need to introduce an abstraction that decouples the high-level and low-level modules from each other.

Based on this idea, Robert C. Martin’s definition of the Dependency Inversion Principle consists of two parts:

- High-level modules should not depend on low level modules. Both should depend on abstraction.

- Abstraction should not depend on details. Details should depend on abstractions.

Here is an example of a PasswordReminder that connects to a MySQL database:

class MySQLConnection {

public void connect() {

// handle the database connection

}

}

class PasswordReminder {

private MySQLConnection dbConnection;

public PasswordReminder(MySQLConnection dbConnection) {

this.dbConnection = dbConnection;

}

}First, the MySQLConnection is the low-level module while the PasswordReminder is high level, but according to the definition of D in SOLID, which states to Depend on abstraction, not on concretions. This snippet above violates this principle as the PasswordReminder class is being forced to depend on the MySQLConnection class.

Later, if you were to change the database engine, you would also have to edit the PasswordReminder class, and this would violate the open-close principle.

The PasswordReminder class should not care what database your application uses. To address these issues, you can code to an interface since high-level and low-level modules should depend on abstraction:

interface DBConnectionInterface

{

public void connect();

}The interface has a connect method and the MySQLConnection class implements this interface. Also, instead of directly type-hinting MySQLConnection class in the constructor of the PasswordReminder, you instead type-hint the DBConnectionInterface and no matter the type of database your application uses, the PasswordReminder class can connect to the database without any problems and open-close principle is not violated.

class MySQLConnection implements DBConnectionInterface {

@Override

public void connect() {

// handle the database connection

System.out.println("Connected to database");

}

}

class PasswordReminder {

private DBConnectionInterface dbConnection;

public PasswordReminder(DBConnectionInterface dbConnection) {

this.dbConnection = dbConnection;

}

}This code establishes that both the high-level and low-level modules depend on abstraction.

Conclusion

In this article, you were presented with the five principles of SOLID Code. Projects that adhere to SOLID principles can be shared with collaborators, extended, modified, tested, and refactored with fewer complications.